Friday, April 2, 2010

Friday, March 19, 2010

CBC News - The National - In Depth & Analysis - How Tolerant Are We?

Nova Scotia: The Mississippi of the North?

CBC News - The National - In Depth & Analysis - How Tolerant Are We?

CBC News - The National - In Depth & Analysis - How Tolerant Are We?

CBC News - The National - In Depth & Analysis - How Tolerant Are We?

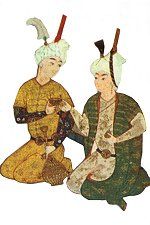

Shama'il al-Muhammadiyya

As salaamu 'alaykum.

On the eve of every jumu'a (Thursday night), I will post one prophetic tradition from imam Tirmidhi's, Shama'il al-Muhammadiyya. Learning about the prophet's characteristics, is an obligation upon every Muslim. One cannot truly love God without first loving His Rasul (sallallahu 'alayhi wa salaam). In order to love something, one must know all there is to know about the object. By learning about our Liege-Lord Muhammad's (sallallahu 'alayhi wa salaam) physical traits and manners, we will ascend in maqamat (spiritual ranks), thus, attaining the title of insan al-kamil (the perfect man).

May Allah ta'ala give us all tawfiq.

(1) HADEETH NO. 1.

Anas (Radiallahu Anhu) reports: "Rasulullah (Sallallahu alaihe wasallam) was neither tall nor was he short (like a dwarf--He was of medium stature). In complexion, he was he was neither very white like lime, nor very dark, nor brown which results in darkness (he was illuminant, more luminous than even the full-moon on the 14th night).

The hair of Rasullullah (Sallallahu alaihe wasallam) was neither very straight nor very curly (but slightly wavy). When he attained the age of forty, Allah the Almighty granted him nubuwwah (prophethood).He lived for ten years in Makkah (commentary) and in Madina for ten years. At that time there were not more than twenty white hair on his mubarak (blessed) head and beard." (This will be described in detail in the chapter on white hair of Rasulullah (Sallallahu alaihe wasallam).

COMMENTARY.

Sayyidina Rasullullah (Sallallahu alaihe wasallam) was of a medium stature, but slightly taller. This has been reported in a narration from Sayyidina Hind bin Abi Haalah (Radiallahu Anhu) and others. An objection may arise concerning these two hadith, that it is stated in one hadith that when Sayyidina Rasullullah (Sallallahu alaihe wasallam) used to stand up in a group, he appeared to be the tallest among them. This was not due to his height, but was a result of a Mu'jizah (Miracle). In the manner that no one had reached a higher status than Sayyidina Rasullullah (Sallallahu alaihe wasallam) in `Kamalaate Ma'nawiyyah', (super intellectual status) likewise in the `Surah Zaahiri' (outward appearance) no one could excel him.

It is stated in the hadith under discussion that Sayyidina Rasullullah (Sallallahu alaihe wasallam) lived for ten years in Makkah Mukarramah after nubuwwah (prophethood). For this reason it is stated that he attained the age of sixty years. This is contrary to what has been reported in the other ahadith, where it is stated that Sayyidina Rasullullah (Sallallahu alaihe wasallam) lived there for thirteen years and attained the age of sixty three years. In some ahadith it is stated that Sayyidina Rasullullah (Sallallahu alaihe wasallam) attained the age of sixty five years. At the end of this kitab all three ahadith will be quoted. Imam Bukhari (R.A.) says:

"Most narrations show that Rasullullah (Sallallahu alaihe wasallam) lived for sixty three years." The 'ulama (scholars) have summed up these ahadith in two ways. First, that Sayyidina Rasullullah (Sallallahu alaihe wasallam) received nubuwwah (prophethood) at the age of forty and risalah three years thereafter, and after that he lived for ten years in Makkah Mukaramah. According to this, the three years between nubuwwah and risalah have been in the hadith under discussion.

http://www.inter-islam.org/

Thursday, March 18, 2010

The Sensibilities of Essay Writing

For my Literature and Sensibility course, I've decided to write my paper on William Hogarth's famous eighteenth century engravings, A Harlot's Progress. For those of you who have never heard of Hogarth or his works, I suggest you look him up on good ol' Wikipedia. However, in brief, his six engravings tells a tale of a beautiful, young woman who leaves her native village for London in search for honest work. However, upon arriving to her destination, she is manipulated into working as a prostitute, thus, diminishing her virtue as well as her physical beauty. Throughout the engravings, viewers will come to notice how her once pure white face deteriorates as she becomes plagued with venereal diseases. I know, gross!

Anyways, it consists of six paintings with their own literary descriptions. So if you like reading or hearing stories about women selling their bodies to dirty rich white men, and contracting syphilis, then enjoy!!

sigh......goras!

Coffee — The Wine of Islam

Most modern coffee-drinkers are probably unaware of coffee's heritage in the Sufi orders of Southern Arabia. Members of the Shadhiliyya order are said to have spread coffee-drinking throughout the Islamic world sometime between the 13th and 15th centuries CE. A Shadhiliyya shaikh was introduced to coffee-drinking in Ethiopia, where the native highland bush, its fruit and the beverage made from it were known as bun. It is possible, though uncertain, that this Sufi was Abu'l Hasan 'Ali ibn Umar, who resided for a time at the court of Sadaddin II, a sultan of Southern Ethiopia. 'Ali ibn Umar subsequently returned to the Yemen with the knowledge that the berries were not only edible, but promoted wakefulness. To this day the shaikh is regarded as the patron saint of coffee-growers, coffee-house proprietors and coffee-drinkers, and in Algeria coffee is sometimes called shadhiliyye in his honor.

| The beverage became known as qahwa — a term formerly applied to wine — and ultimately, to Europeans, as "The Wine of Islam." It became popular among the Sufis to boil up the grounds and drink the brew to help them stay awake during their night dhikr. (Roasting the beans was a later improvement developed by the Persians.) |

The Shadhili Abu Bakr ibn Abd'Allah al-'Aydarus was impressed enough by its effects that he composed a qasida (poem) in honor of the drink. Coffee-drinkers even coined their own term for the euphoria it produced — marqaha. The mystic and theologian Shaikh ibn Isma'il Ba Alawi of Al-Shihr stated that the use of coffee, when imbibed with prayerful intent and devotion, could lead to the experience of qahwa ma'nawiyya ("the ideal qahwa") and qahwat al-Sufiyya, interchangeable terms defined as "the enjoyment which the people of God feel in beholding the hidden mysteries and attaining the wonderful disclosures and the great revelations."

The Shadiliyya dervishes were active in the world; it is said that Shaikh Abul Hasan ash-Shadhili, the founder of the order, was reluctant to take on a student who did not already have a profession. It soon became apparent that coffee's benefits could be extended to the workday and the local economy as well. The southern Arabian climate was ideal for coffee cultivation, and the ports of Yemen, particularly the port of Mocha, became the world's primary exporters of coffee.

| They drank coffee every Monday and Friday eve, putting it in a large vessel made of red clay. Their leader ladled it out with a small dipper and gave it to them to drink, passing it to the right, while they recited one of their usual formulas, mostly "La illaha il'Allah..." |

Another early Yemeni Sufi devotional ritual involved coffee-drinking accompanied by recitation of a ratib, the invocation 116 times of the divine name Ya Qawi, "O Possessor of All Strength!" — a prayerful and witty juxtaposition of sound and sense.

| Over time, coffee even acquired an angelic reputation: according to one Persian legend, it was first served to a sleepy Muhammad by the Angel Gabriel. In another story, King Solomon was said to have entered a town whose inhabitants were suffering a mysterious disease; on Gabriel's command, he prepared a brew of roasted coffee beans, and thereby cured the townspeople. |  |

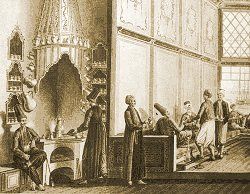

By the early 16th century CE coffee-drinking moved to the secular sphere, and a new institution evolved which transformed social life throughout the Islamic world. Coffee-houses supplied more than beans — they had the needed equipment, the expertise to prepare the brew, and a convivial milieu in which to enjoy it. Ahmet Pasha, the governor of Egypt during the late 16th century CE, actually built coffeehouses as a public works project, thereby garnering great political popularity. In the mid-seventeenth century two Syrian businessmen, Hakm and Shams, introduced coffee to Istanbul, established the city's first coffeehouses, made a fortune in the process, and established a new and profitable arena of economic activity. Evliya Efendi wrote of the coffee-merchants of Constantinople:

Throughout the first few centuries of its history in the Islamic world, coffee's popularity engendered great controversy. Many were suspicious of the effects of caffeine and the gatherings in which it was consumed — they seemed debauched to some and subversive to others. Coffeehouses competed with mosques for attendance, and as unsupervised gathering places for wits and learned men, provided spawning grounds for sedition. The wags of Istanbul jokingly called the coffeehouses mekteb-i 'irfan, "schools of knowledge." Efforts were launched, and persisted for at least a hundred years, to declare coffee an intoxicant forbidden by Islamic law.

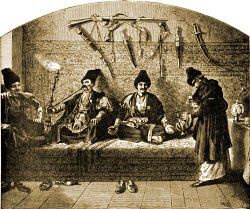

During Ramadan in 1539 CE Cairo's coffeehouses were raided and closed, although only for a few days. Soon after coffeehouses achieved popularity in Constantinople, Sultan Murat IV closed them all; they were to remain dark until the last part of the century. But as soon as the Sultan's edict went into effect, the coffeehouse patrons, their money and their social life, went elsewhere:

| In Brussa there are seventy five coffeehouses frequented by the most elegant and learned of the inhabitants. All coffeehouses, particularly those near the great mosque, abound with men skilled in a thousand arts... These became famous only since those of Constantinople were closed by the express command of Sultan Murat IV. |

The moralists fought a losing battle, for they were opposed by well-educated coffee-drinkers from the highest ranks of the religious and political hierarchy who did not look fondly upon innovative legal prohibitions. The "tavern without wine" offered a respectable gathering place for men to socialize and entertain away from home. Business was especially brisk during Ramadan, when proprietors made extra efforts to draw crowds with storytellers and puppet shows.

Despite coffee's eventual secularization, the fondness for it in Sufi circles and the motives for its use were not lost. Helveti dervishes were among those who enthusiastically drank coffee to promote the stamina needed for extended dhikr ceremonies and retreats. Once coffee was readily available throughout the Ottoman Empire, it became a fixture of daily life in the Helveti dergahs, and a legend was born that linked the beneficial effects of a miraculous spring to a morning cup of brew:

| In Persia, coffeehouses evolved into hotbeds of lasciviousness and political dispute soon after they were introduced. Shah Abbas I responded to this situation by installing a mullah in the leading Isfahan establishment; he would arrive early in the morning, hold forth on topics of religion, history, law and poetry, then encourage those assembled there to be off to their work. A pious ambience was thereby promoted, an example was set for other coffeehouses, and a potentially volatile social milieu was somewhat controlled. Poets and mystics occasionally took up permanent residence; for example, Molla Ghorur of Shiraz settled in Isfahan in his old age and established himself at a coffeehouse, which soon became a gathering place for those seeking spiritual guidance. |  |

The 17th Century French traveler Jean Chardin gave a lively description of the Persian coffeehouse scene:

| In private valises, coffee reached Venice in 1615, Marseilles in 1644, and London in 1651; but it did not make its official debut into European high society until 1669, when it was introduced to Parisians by the Turkish ambassador, Suleyman Mustapha Koca. By the end of the century coffee was fashionable throughout Europe, and its cultivation and use subsequently spread to North and South America. Wherever it has been introduced it has become a symbol of hospitality and a vehicle of sociability. The current resurgence in popularity of the coffeehouse is undoubtedly a response to the aggressive marketing efforts of coffee producers and enterprising restaurateurs. It may also contain a longing for the sort of companionship the Shadhiliyya dervishes enjoyed six hundred years ago, as they gathered to remember Allah and passed the cup from hand to hand. |

http://www.superluminal.com/